Helping Students Track Attendance and Engagement

The third in a series of posts about the progress tracker for my ungraded course

Over the last few weeks, I’ve been discussing the Progress Tracker I developed for my Writing 101 course. In my previous post, I talked about helping students track their learning tasks. Here I’ll discuss course attendance and engagement, how I’m encouraging it, and how students are keeping up with it. This will be a long one; it’s a thorny problem.

Attendance Woes

Almost every instructor I talk to these days is struggling to motivate students to attend class—either that, or they’ve totally given up. I haven’t given up, but last semester made me want to. By the end of the semester my already small class of 12 had dwindled to 4-5 regular attenders, with others showing up with varying degrees of frequency.

Probably the most common way of dealing with this problem is to create an attendance policy that penalizes students for missing class. That’s certainly one way to encourage regular attendance, and I do think such requirements motivate some students to stay on track. But they also introduce a number of problems.

In the last year alone, I’ve had students with COVID or other contagious diseases; students with chronic illnesses; students coping with physical traumas (more than one with a concussion in a relatively small sample size!); students enduring psychological traumas or serious mental health problems; students who are grieving losses of friends and family members; students dealing with family emergencies that take them far away from campus; and those who simply struggle with the demands and pressures of college life, balancing curricular and extracurricular commitments, or living independently for the first time.

In all of these cases, students have had to be away from class for days, sometimes weeks, at a time. And in all of these cases, I have received profusely apologetic student emails sent from hospitals, roadsides, airports, funeral homes, and every imaginable place pleading for mercy on their course grades—sometimes with gnarly photos intended to verify the student’s claims about their inability to attend class. And I don’t even have a strict attendance requirement.

I think we’re all familiar with these emails, but I find them deeply disturbing. We would never expect our work colleagues to lay their lives bare in this manner or to be concerned—as they stand at the caskets of their loved ones or climb out of the wreckage of a totaled car—about what work they owe us. It is a deeply dehumanizing thing to expect of another person. And yet, even when we don’t expect it, students still feel the need to assure us that they haven’t forgotten about the class, that they’re doing their best, that they’ll still get that essay in, that they’re very, very sorry for the inconvenience.

Students didn’t develop this habit on their own; we trained them in it. They wouldn’t send these emails if they didn’t think we expected it. Somewhere along the way, they got the idea that no matter what extenuating circumstances arise, they must comply with the course policies or be punished with a bad grade. They got the idea because that’s what we told them would happen. By and large, it’s what has happened.

It’s because of these students (and I have a handful every semester) that I don’t have an attendance requirement. I don’t want a student in the middle of a crisis to be thinking about my class. I want them to be thinking about their own healing, or that of their loved ones. And they can’t think about healing if they’re forced to beg me for mercy whenever something goes wrong.

I stand by this policy. But I know what many of the skeptics out there are thinking, because it’s what I’m thinking some of the time. They’re thinking that most students who are chronically absent aren’t undergoing a crisis—they simply don’t want to attend class for one reason or another. And those students don’t need endless flexibility and compassion: they need some kind of penalty or reward to motivate them to do the right thing for themselves. An attendance requirement is for their own good.

I do think we should expect regular class attendance and do everything we can to encourage it. But I’m not so sure that most students who skip class are lazy or don’t care. The truth is that I simply don’t know why students skip class unless they tell me, and I’ve been wrong in my assumptions about this before. Sometimes I’ve found that a student I assumed to be lazy or apathetic was actually in crisis. Or else they were making calculated decisions about what academic activities to prioritize based on the amount of time available to them and the work they think will be most useful to them in achieving their goals. Attending my class, apparently, didn’t clear that bar.

Even if we assume many students are simply lazy or apathetic, I’m not sure how much a grade penalty for missing class will motivate them. In fact, I’ve seen it de-motivate a number of my previous students. They miss so many classes, through emergency or simple negligence, that they find themselves at the level of a C or D. And rather than put in the effort to complete the course, they simply drop off the map—even if they were doing decent work beforehand.

And even if absence penalties do motivate students to attend class, we have to ask ourselves at what cost. Sometimes these policies encourage students to come to class when sick. I don’t have an attendance requirement, and I’ve still had students with communicable diseases come to class when they should be at home. Sometimes these policies encourage students to attend class when they are not in the appropriate mental headspace to get anything out of it. Rather than a room full of learners, we end up with a room full of attenders, whose begrudging presence makes it difficult to teach. Which leads me to my next point.

Participation Woes

I have similar misgivings about participation requirements. Of course we want students to participate actively in class, even when they find it difficult. For my course context, that means primarily, but not exclusively, speaking at some point during our class discussions and activities. Once again, the most common way to encourage this is making “participation” part of the course grade, often by specifying how many times students should speak in class. And once again, this sometimes produces undesirable effects.

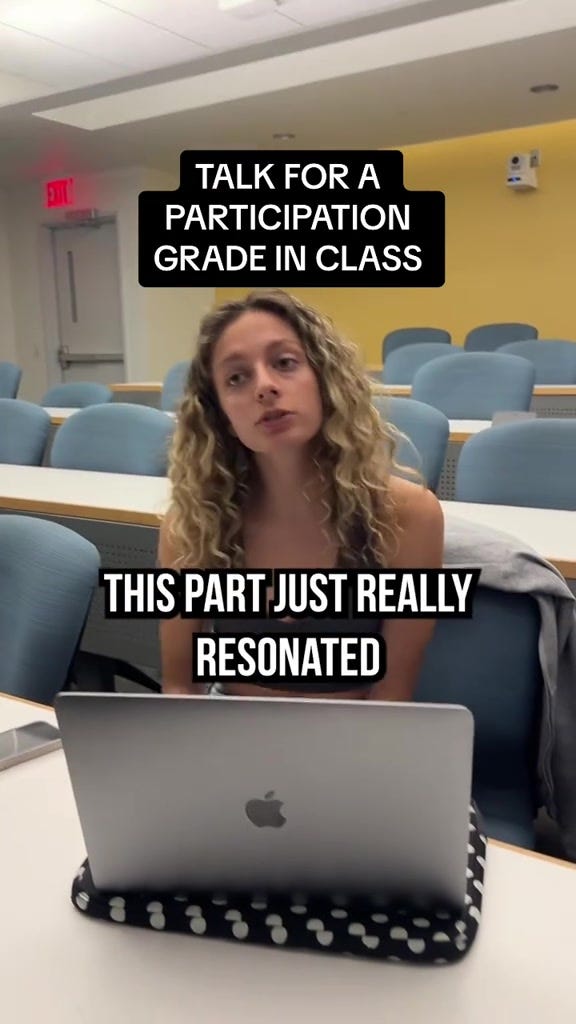

The first is that some students start to view participation as a task to be completed rather than a general orientation to adopt toward class time. That is, they start talking for the sake of talking rather than authentically engaging. Students are aware of this dynamic, and I don’t think they like it any more than we do:

The dynamic is especially evident if participation is quantified. Students speak, as assigned, one or two times, even when they feel they have little to contribute, and then tune out for the rest of the class. Or else they’re so focused on how and when to speak that they find it difficult to be fully present for the conversation taking place.

Additionally, when we indicate that participation is primarily speaking during class, we risk facilitating a discussion that is mostly talking and very little listening. And those students who are good listeners, who take time to process information, who dislike being forced to speak before they have something to say, are at a disadvantage. This is to say nothing of neurodivergent students who may struggle to participate or engage in the ways we find traditionally acceptable. There’s nothing worse than dinging an otherwise engaged and thoughtful student on a participation grade just because they don’t relish the idea of speaking in front of others.

The skeptic in me, and probably in you, objects that participating in a discussion is a valuable skill, and reluctant students need to be gently, but firmly, asked to do so. But I wonder, again, whether a participation grade actually accomplishes that goal. In many cases, students who don’t wish to speak in class simply opt to get dinged on their participation grade rather than contribute verbally to discussion. Clearly, the grade is not enough on its own. And it may be counterproductive to the environment we’re trying to create.

Some Attempts at a Solution

So, we want students to attend class regularly and engage in class while they’re there. But penalizing them for lack of attendance or participation has its own problems. How do you encourage attendance and participation without punishing or rewarding students through grades and points?

I wish I had the answer. We’re not in control of every contributing factor to the engagement problem; there are many external circumstances and systemic constraints that thwart our attempts to solve it. However, I think there are some things that can help.

Last semester my attendance was abysmal and class participation was only okay. While things have not been perfect this semester, they have been considerably better. This may be due to a number of factors, like a different student population or the fact that it’s fall instead of spring. It may be due, in part, to my course policies. Here are some things I’ve tried:

Replacing “participation” with “engagement”

This is not a change from last semester, but it’s something that has helped me be more precise with myself and my students about what I expect from them both in and outside of class. In the Attendance and Engagement section of my progress tracker, I clarify what I mean by “engagement”:

Being engaged in class means attending class every time you’re able; coming to class prepared for the day’s activities; contributing regularly to small- or large-group discussions; being a good classroom citizen by supporting your peers and abiding by our discussion guidelines; submitting work that represents your best effort, in a timely fashion; and submitting work that is your own, not someone else’s.

(Next time, I may add a line about seeking out feedback at the Writing Center or during office hours to improve your work.)

I want to convey that attendance and “participation” mean more than just putting your butt in a seat and offering an arbitrary comment or two. Being engaged means putting forth your best effort to be really present, physically and mentally, with the course each time you come to it. Engagement will look a bit different for every student, and I try not to make assumptions about who is and is not engaged at any particular moment. I think the definition above offers a good general picture.

I also want to invite reticent students to step out of their comfort zone without forcing them. So the discussion guidelines referenced above, which we establish as a class in the first week, note that good discussions require more than just a series of intelligent-sounding disquisitions; they require active listening and discussants who can offer thoughts, questions, and provocations even when they’re not fully formed. During our midsemester conferences, I do try to encourage quieter students to speak up more often. I think what helps more than anything is when I assure a student that they have interesting and relevant things to share, and that sharing those thoughts, to the extent they’re able, will benefit the rest of the class. It’s not just about getting them to talk; it’s about ensuring that the classroom community can gain from the great things they have to contribute. This doesn’t work every time. But when it does work, it’s pretty amazing.

Helping students set good goals

Since engagement looks a bit different for everyone, and since students will struggle with different aspects of engagement, I ask them to set their own personal goals and evaluate themselves on their progress toward these goals throughout the semester. While I did have students do this in the first week of class last semester, I didn’t offer guidance about how to do it well. As a result, many of the goals students set weren’t particularly helpful. Goals like “participate in class” or “have good attendance” don’t offer very clear or specific guidelines for how students should approach the rest of the course.

This semester, I asked students to do a brief activity in the first week of class that would help them set better goals and then record those goals on the progress tracker. This seemed to help. And I’m looking forward to hearing them speak about whether or not they accomplished their personal goals in our final grade conferences this week. My impression, so far, is that many students did reach the engagement goals they set for themselves 15 weeks ago. And those who didn’t may be able to draw important lessons from their experiences this semester.

Providing ways for students to track, self-assess, and align expectations around attendance and engagement

This is, of course, one of the main goals of the progress tracker itself: students can set their goals, keep up with class attendance, and make notes about engagement. It’s also a great tool for helping students self-assess their progress and then align their expectations with mine.

At our midsemester conferences, I asked students to talk to me about their course attendance and engagement, and I think having the progress tracker helped them evaluate their efforts more accurately. Last semester, students seemed surprised when I told them just how many class days they had missed according to my records. This semester, I saw less of that. The progress tracker offers students their own clear records, so there are no surprises for either of us.

The midsemester conference also provided a chance for us to align expectations around attendance and engagement. If students were missing lots of class but indicated that they hoped to achieve a high course grade, we had a chance to talk about why attendance was important to their learning and set some goals to make their attendance more regular. If students weren’t contributing to class very often, we had a chance to talk about what kinds of support might help them participate more frequently.

Evaluating attendance and engagement holistically

This is what allows me to be flexible with students in crisis or whose engagement in the course does not look like what we’ve traditionally expected. If a student missed two weeks of class because of an illness or emergency but was otherwise present and engaged—no problem. If a student was in class every day, prepared and paying attention, but they didn’t speak up much during large group discussion—no problem. If they’ve put forth their best effort to be present and engaged, that’s what really matters.

This does, of course, require me to trust students when they evaluate themselves on attendance and engagement. If they tell me that they had an emergency requiring that they miss two weeks of class but don’t provide more specifics, I respect that. If they tell me that speaking during class is very difficult for them but they did their best, I believe them. We certainly discuss any negative consequences of course absences or lack of participation: if aspects of their work in the course suffered from it, we take that into account. But a crisis or inability to participate in ways we have traditionally expected will not tank students’ chance of success in the course. In general, I’m honest with students about these matters, and I believe that they’re honest with me.

In order to make this kind of honesty possible, we of course have to work on building trusting relationships with each other. But that’s a topic for another day.

Next week, I’ll talk about how I’m helping students track the most important part of the course: learning and growth. Stay tuned!

Emily, another phenomenal piece! I too shifted from the phrasing "Participation" to "Engagement"--it was years ago and well before I was doing any sort of ungrading, though. If I recall correctly, I was inspired by Susan Cain's book Quiet and its arguments on how the classroom is set up to reward extroverts and punish introverts through structures like participation points. At any rate, so much of what you're describing here resonates; looking forward to the next installment!

I’m fighting the good fight with high school attendance too. Sigh.